During our latest submission period, the stories came pouring in as they usually do. Hundreds of them in just a week or two, a thousand or more before the period ended.

During our latest submission period, the stories came pouring in as they usually do. Hundreds of them in just a week or two, a thousand or more before the period ended.

Every writer who submitted poured their heart into those pages, hoping their story would be one to catch our attention. But here’s something not every hopeful contributor understands: in that sea of submissions, most of our decisions are made in the first three pages.

That may sound brutal, but it’s not about looking for a reason to reject stories. It’s about the practical reality of time, capacity, and what it means to compete for a reader’s attention in today’s world. Your opening isn’t just your introduction. It’s your handshake, your elevator pitch, your proof of concept. It’s the moment we decide whether your story moves forward or we stop reading right there.

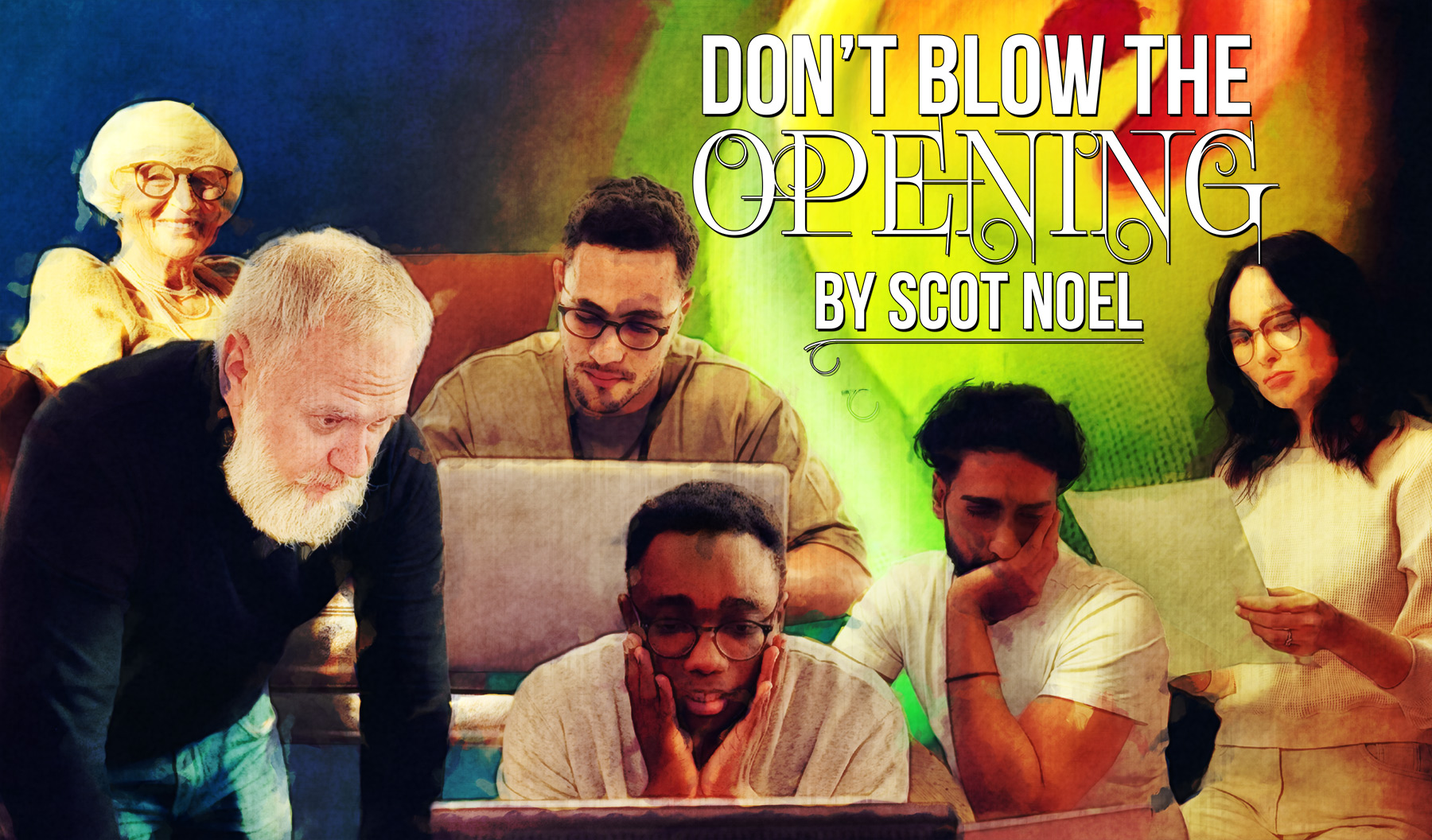

This is a behind-the-scenes look at how we, the First Line Readers and the editorial team at DreamForge, evaluate story openings. What makes them work (or fail to), and how did we adapt our review process this reading period to deal with the flood of stories? More importantly, it’s about giving you a clear sense of how to make your story stand out where it matters most: at the beginning.

How We Actually Read Stories

DreamForge typically receives between 700 and 1,000 stories during an open submission period. Those stories are reviewed by a First Line Reader crew of 16 to 18 volunteers, plus editorial staff. Each story is logged, checked out, and evaluated— but not every story gets a full read. That’s not because we’re cold or uncaring. It’s because there are only so many hours in the day.

Some quick math explains a lot. Even if we spent just five minutes per story, that’s over 83 hours of reading. Realistically, reading a 3,500-word story takes 20 minutes. Multiply that across all the stories we receive, and we’re talking about hundreds of hours of work. Now consider the desire of many of our contributors to write 4,000-to-7,000-word stories, and it’s easy to see why a magazine like ours needs an efficient way to triage incoming works.

To help streamline the workload this year, we added a logline requirement. That means a brief description of the story’s premise in a few sentences. The logline isn’t graded on grammar or polish, and no story is rejected for having a bad logline. It’s simply a way to tell whether the story fits the kind of fiction we publish. For example, if your logline clearly signals body horror or a murder mystery, apocalyptic dystopia or government conspiracy, we can see right away that it’s not the right fit for DreamForge. That saves us time, and it saves writers from a slow rejection.

But even when a story fits thematically, that doesn’t guarantee it will move forward. The real test is the opening — those critical first 1–3 pages.

Why the Opening Matters So Much

We know many writers, especially newer ones, expect their entire story to be read and considered. We wish that were possible. But the reality is that editors and readers (not just at DreamForge, but at almost every publication) make decisions quickly. If the opening doesn’t pull us in, we have to move on.

When a story does move forward, it’s usually because the opening achieved a few key things:

- It oriented us quickly and clearly.

- It introduced compelling characters.

- It presented something happening — an inciting incident.

- It gave us a reason to care.

It doesn’t have to be perfect. It does have to be effective. If a story stumbles badly in those opening moments, we can’t hold it and say, “Maybe it gets better later.” Someone else’s story is already strong from page one. That’s the competition.

What We Look for in a Strong Opening

Let’s break down what actually makes us lean into your story in those early pages.

1. Orientation: Where Are We and Who’s Here?

Think of the first moments of a live play. The curtain opens. In a few lines of dialogue or a few stage cues, you know where you are, who’s on stage, and what kind of story you’re in. That’s exactly what a good opening does on the page.

We should have a clear sense of:

- Who the point-of-view character is,

- Where they are,

- When we’re in (present day, near future, deep space, magical forest), and

- What they’re doing.

You don’t have to explain everything. In fact, you shouldn’t. A light, elegant touch is best: just enough for the reader to feel oriented and grounded in the scene. If we feel like we’re floating in a white room with no sense of time or place, it’s hard to care what happens next. The same is true if the reader is fed paragraph after paragraph of detail and background. Remember, a light, graceful touch is best.

2. Character: People Before Plot

Right from the start, we need to see something of a character’s personality. Not a resume. Not a paragraph of backstory. A moment. A choice. A line of dialogue. A detail that hints at who they are and what matters to them.

Even more important is a hint of vulnerability. Readers are drawn to characters with flaws, weaknesses, or desires that can be stress tested by the story. If your characters arrive fully formed and flawless, they have nowhere to grow.

We also need clarity on who the protagonist is. One of the most common issues we see is an ensemble cast with no clear lead. If everyone’s introduced equally, we don’t know whose journey to invest in. (ensembles can be done well, but usually not by beginners).

3. The Inciting Incident and the Narrative Hook

Something should happen, and it should happen early. At the bottom of page one or top of page two, the story should give the protagonist a reason to act. It doesn’t have to be a world-ending explosion. It could be a discovery, a disruption, a surprise, a moment of unease. But it should be something that pulls the character into motion.

The narrative hook goes hand-in-hand with the inciting incident. It’s what makes that incident personal. A mysterious signal might be interesting. But if that signal is coming from the protagonist’s long-lost sister, now it matters. It touches the character’s inner life, not just their surroundings.

Without that personal stake, the story may wander without urgency— and that’s a big reason why many submissions stall early.

4. Avoiding Common Pitfalls

We see certain patterns over-and-over in stories that don’t make it past the first few pages. Here are the biggest red flags:

- Exposition dumps: The writer spends paragraphs explaining the world or a character’s backstory instead of giving the reader an experience. (We call it “staying with the experiential moment.”

- No clear protagonist: The story introduces several characters but no focal point.

- Low or no stakes: Nothing seems to matter to anyone.

- Passive characters: Characters observe events but don’t make meaningful choices.

- “White room” openings: We have no sense of place or situation.

Any one of these problems can be a concern. Several together are usually a hard stop.

A Real Example: The Bone Yard

To help illustrate these issues, we created a teaching story called The Bone Yard. It’s not a real submission, but it’s based closely on one we received this reading period. Instead of calling out the author, we re-engineered it to preserve the structure and problems we saw, changing a fantasy into a science fiction adventure — and added editorial notes to highlight what’s going wrong.

On the surface, The Bone Yard seems promising:

- It opens with sensory detail and a clear setting.

- It orients us to the characters and the location.

- There’s something unusual happening — a ship hull shimmering in strange light.

But look closer, and the cracks appear fast.

- There’s no clear protagonist. We meet three characters at once, all treated equally.

- They have no personal stakes. The shimmering ship isn’t tied to anything personal or urgent.

- Their responses are passive. They’re tourists, not problem-solvers.

- The story stalls in exposition as it dumps backstory for hundreds of words.

Nothing engages the characters into acting. Nothing makes the moment matter to any one of the characters or to all of them collectively. And without that, even a technically well-written story can lose its grip on the reader.

That’s why The Bone Yard is now a tool for our First Line Readers. It gives us a common language for talking about openings. And for writers, it’s a way to see where stories falter before they’ve really begun.

Why Even Good Writers Stumble Here

This isn’t just an issue for beginners. Experienced writers can trip up at the starting line, too. Why? Because it’s easy to fall into a few seductive traps:

- Believing the story will explain itself later.

“Just wait until page 7 — it all comes together!” Unfortunately, no one’s waiting that long. - Falling in love with backstory.

You spent days dreaming of and building out your world. You want to share it all. But the reader doesn’t need the entire history of your starship program on page one. They need a person in motion. - Assuming readers will care just because the idea is cool.

A shimmering spaceship, a haunted forest, an alien market — these can all be great settings. But without human stakes, they’re just colorful wallpaper. - Hesitating to commit to a protagonist.

Trying to keep options open or introduce everyone equally often leaves the reader unmoored. It’s okay to have an ensemble, but we need one clear focal point to carry us into the story.

These are fixable problems. But they’re also story-killers if left unchecked.

How We Decide What Moves Forward

Because we can’t give every story a full read, the editorial team often uses a layered approach:

- Logline and fit check. If the premise clearly doesn’t match what we publish, it’s declined early.

- First 1–3 pages. If the opening is strong, the story moves on. If it’s weak, we stop there.

- Sample read. For stories that show promise but need evaluation, we might also check a middle scene and the ending before deciding if it warrants a full read.

- Full read. Reserved for stories that have already demonstrated strong craft and fit.

This process is only in part about finding flaws. It’s about finding the stories most likely to resonate with our readers and our theme: stories that make us want to keep turning pages. (I’ll risk confusing the matter entirely by revealing that flawed stories still sell, but that’s often because the writer knows exactly what rules they are violating and how to do it, and the work itself demonstrates a unique strength even well structured stories lack.)

Don’t Fear the Gate — Master the Threshold

We know this process can feel intimidating, especially if you’re an emerging writer. But our goal isn’t to scare anyone off. We want to see you succeed.

Think of the opening as your threshold. You don’t need to show us everything. You just need to make us want to walk through the door.

Download the Teaching Story

We’ll be updating The Bone Yard over time, eventually turning it into a full annotated story from beginning to end. It’s a living example of what goes wrong — and how to do better.

Download The Bone Yard Teaching Story (PDF)

Keep writing and realize that even when we send your story back, we’re rooting for you to succeed. We look forward to seeing your name again in our submissions queue and we hope that next story shows you are indeed honing your craft.