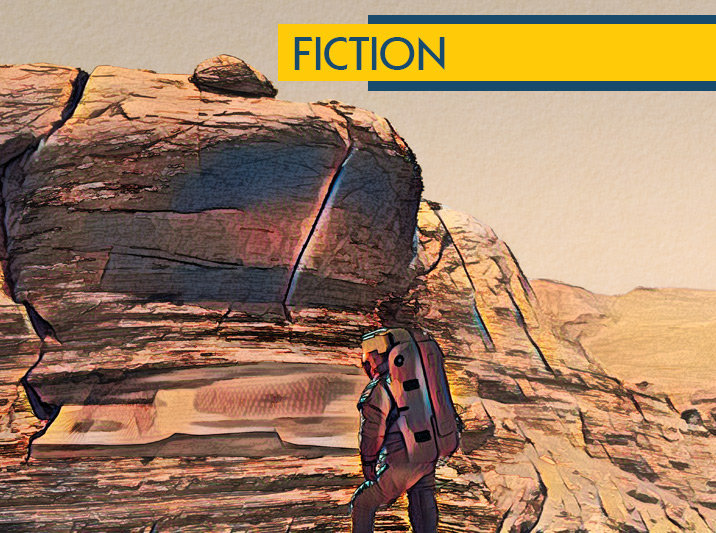

It looked like a fish. The rock around it was rough and shaley-looking, but right there it looked like someone had swiped a smooth hand across the surface when the rock was soft, then thumbed coarse overlapping fish-scale patterns into it, as a potter would decorate some clay.

Or, Nu thought, it looked like the cliffside had been smacked by the flank, fins and tail of a fish with scales so much harder and hotter and more alive than rock that it was able to leave an indelible print as long as her arm.

She smelled the deadness of her recycled air supply, feeling the dusty crust of Mars crunch under her boots as she turned to gaze around her and up at the twilight— there where the ruddy clifftop edges were softened by gray light far above. Her suit temperature, when she checked, was normal, but in spite of the cocoon she wore she felt the frigid silence of this place just beyond it. And the desperate dryness. The thought of a fish here, its body undulating and its tail flashing in Martian water, was wondrous to her. Impossible.

Right now, it was also weirdly comforting.

Her Inuit childhood, like a hoarded dream, came back to her. You can feel the truth. What do you feel? The shaman spoke to her. And dutifully she answered: I feel the spirit of the fish, still living before me.

She used her wrist camera to take a dozen photos and a few holos. Then abruptly she felt the thickening darkness begin to close in and choke her. Perrin filled her mind. Not the first time Nu had felt her presence since her death. She resisted it now. Perrin? She’s not here. In my mind. She turned to hasten back downslope toward the research kite.

She also wasn’t the first geologist to find fossil traces on Mars. This find, if it was one, would not rock the galaxy. It wouldn’t bring Perrin back and it wasn’t dramatic enough to protect her grant from being withdrawn by Mars Corporation Industrial Research. But she was going to continue her work until she received the notice and a homebound flight assignment.

Inside, in the ship’s electronic log, she hastily entered this site on the map, attached photo and holo images and keyed in some notes.

Darkness had fallen by the time she finished. She wanted to be gone, badly. But preservation of research information was 50 percent of her training, so she swallowed her lifetime repugnance for the dark, in which unsatisfied spirits might be wandering miserably.

Nu realized she was gritting her teeth as she prepared the kite’s cabin, started the engine, and rose out of this sandy ravine past the cliffs and out into the open again. She began to breathe normally only when she saw the lights of Mars Colony 3 far ahead.

“291 Returning to British Science Three,” she told the dispatcher.

“Find anythin’ good?” It was Brand’s Cajun-American drawl.

“Nothing worth talking about,” she said.

“Aw,” he grumbled. “More luck tomorrow, Nu.”

If there was one. The notice could be in her mailbox now.

Once her kite was ensconced within the motor pool Small Vehicles hangar, she walked the short gravelly roadway to British Science Three quarters. Bright entry lights ahead obscured the Martian skyscape— all but busy Deimos shuttling across the darkness far above.

She entered the outer airlock doors; after the airlock admitted her, she opened her helmet to the inside air but left it on her head, hoping to get through the message center and dining room, and into her own tiny quarters, before she was recognized.

When she saw the new Mars Corporation scientist enter the hallway at the other end, she immediately turned left, down one side of the quadrant of staff rooms. Like the others, her door opened toward a central square containing dining and recreation areas and research libraries.

Nu closed and locked her room. She took off the helmet and sat. She heard Brand, in memory: “It warn’t your fault about Perrin.”

Of course it wasn’t. But her instincts were still strong, after all these years. Feeling that Perrin was alive somewhere, she was responsible until the matter was settled.

In memory she heard the shaman instructing her in the winter dark, while Arctic cold bit at her nose and even at her small fingers nested together in the fur of the tunic sleeves. Her breath surrounded her with puffs of cloud. Like a curtain before the bright roadway of stars, the Aurora Borealis arced above the two of them, magnificent blue and green, menacing.

What do you feel? The shaman said. Trembling, she replied: I feel the spirits of my ancestors above me.

She was no child now.

Years away from the shaman and enormous distances from Earth, Ticasuk Nu was here at the experimental Mars colony as an award-winning research scientist, to discover what secrets Mars kept in its belly, under the skin.

The secrets that had she had not found, so far.

Here two years without success, and her research partner dead in an accident that seemed preventable. These had provoked the corporation to review her status and her grant. She had heard rumors.

She was no longer a child. Still, now as she unsuited, the shaman’s spirit seemed to be printed in her mind. And it repeated: You can feel the truth. What do you feel?

Dutifully she answered: I feel the spirit of Perrin, alive in the darkness somewhere.

In the darkness, crazy with fright.

When she woke, well before daylight, she found that she had slept supperless in her undersuit amid scattered sketches and notes, with her tablet’s cold light shining on her face.

The thought process that had kept her hunting through half of the night was gone, now. Surely the notes would remind her of the trail of thoughts, but the place where the trail had taken her, herself, was as clear as the brilliant arctic sun on fields of snow.

What do you feel?

She answered dutifully, That as we began we will end. Perrin and I.

Her own answer startled her. But she had waked knowing what to do next. It was like the feeling that the ice was too thin to walk across. Like the feeling that it was time to migrate to the grassland for summer. Or that a wolf was near.

Nu loaded her pack with the research items she might need. She put on a fresh undersuit and socks, everything clean and new: each one donned in the eerie light with a sense of ceremony. And then her suit, pack and helmet. She locked herself out of her quarters.

Deliberately passing her mailbox without looking, Nu entered the dim light of the British Science Three 24-hour kitchen and loaded two thermal bags with a few days’ worth of food in packets and bars and sealed containers. She exited British Science by a utility airlock, avoided most of the security cams, then strode off down the gravel road to the hangars.

“Starting early?” the motor pool attendant asked.

“Yes. When he finally clocks in,” she joked, “Tell the dispatcher I have research to wrap up today.” That message, that she was finishing up, should keep others waiting patiently for her return instead of interrupting her, even for days.

The attendant took down her message, helped her turn and set the kite, then watched as she loaded and brought up the lights inside and readied the cabin. The elation she always felt, as the kite burst upward into the air, carried her away.

As she neared yesterday’s site the distant sun was rising across this scorched and bare part of Mars. Abruptly she allowed the thought to enter her mind: She missed Rose Perrin.

That was the simple truth. They worked together well, geologist and paleontologist. Maybe, as Brand hinted, it had something to do with their backgrounds— Perrin was half Cherokee, as well as part Irish and whatever else. Her dark hair and eyes were twins of Nu’s, although Perrin’s hair was curly, and she had freckles.

Nu shrugged. Genes were nothing really; just the surface. What she and Perrin really shared was a kind of gift for listening as they researched— listening to the voice of what they were studying, and sensing what was there, as well as measuring and recording. They both seemed to feel the voice in these Martian cliffs and valleys. It was not what anyone would call a scientific view of things. They mentioned it to no one else.

But once, a month or two ago, Perrin had said as they landed, There’s something holy and broken here on Mars. Nu had nodded. There was.

There is. She nodded again now.

And now Perrin’s broken body, crushed by falling rock, lay enclosed and preserved in a vault at the Colony 3 port, waiting to be shipped to her family on Earth.

Nu had enough light to visually locate the deep ravine where she had landed yesterday. She let the kite descend into it again.

This was their latest site together. Until yesterday, Nu had been unable to make herself return here. From the air this terrain looked like an ancient riverbed, and in fact like the bed of a pretty deep and fast-flowing river. They had come to this ravine hoping to find geological signs, or fossil signs, which would confirm that water had flowed here once.

Of course, the Corporation was most interested in the economic potential of this area— of developing the land here somehow. Their assignment from British Science was to discover whatever was here to be found, but the commercial value of their work, the hope behind their grant funds, lay in finding something in soil or rock —oil, gems or gold, uranium or titanium— that would make development attractive.

Perrin had gone upslope, that day a month ago, searching for fossilized plant remains that might be signposts. Like following a trail. Nu stayed below to trace some unusual layering of the rock deep in the ravine.

Perrin’s chisel and the crack it made, probably a tiny one, must have been all it took to loosen the weight of the sloping face above her and let the rock cascade downhill over her. The chisel and mallet were still clutched in her hands when they dug her out.

Today Nu would begin again as a researcher by looking at what was really here, not what was in her mind. It was a way to walk forward away from her own loss and fear. She sat on a rock in the floor of the ravine, sipping her suit’s nutrient feed, remembering Perrin eating lunch with her here the day before her death.

What do you see?

Perrin is not here now.

What do you feel?

She is nearby somewhere.

Nu cleaned up her containers, without haste, and then as if Perrin were with her, surveyed what was visible of the cliffs along the ravine floor, noting spots that seemed to invite a closer look later. Noted. And they could wait.

She located the pathway Perrin had taken when she went upslope. Nu began to climb upward herself along the same route, as if she had decided to go along with Perrin.

Partway up the first slope, she wedged her feet onto a thin ledge and touched a small vertical rock face. Abruptly, in memory she felt the rumbling again, saw single rocks bouncing down the ravine walls while she crouched beneath a low ledge on the cliff wall for protection, her horror deepening as the first sliding tide of rock roared by. Before her now, vivid as life, she saw the bright color of Perrin’s suit fly above her head and out into the air of the ravine, carried in the next descending wave of rock and dust.

Nu clung to the hillside where she stood, quaking with horror. She couldn’t let the memory overcome her while she climbed. She forced it to leave her until she had struggled upward to a flat spot.

There she stopped to drink, panting. There the memory avalanched over her again and again, and then she drank some more and let it happen again. After a while the memory ebbed from her without being forced away.

Nu looked upward, seeking the raw rock face that would show where Perrin’s rockslide had broken off. When her eyes found it, she climbed upward toward it. No jetpack was needed here. Climbing was OK. But she climbed carefully and patiently.

She stood before the new cliff-face, studying it. Again, she saw Perrin carried away in the wave of rock, gripping her hammer and chisel. Nu’s balance left her, and she swayed unsteadily. She squatted, pressing her gloved hands to the ground to keep from falling over, and froze.

What do you feel?

Her grief. The sadness of death.

Instinctively, Nu placed one hand on the newly exposed flank of the rock, to show respect.

What do you feel?

The rock contains great power. It waits proudly for the power to be seen. One who wishes to see it will have to —

She felt vibration in the rock. Like when ice on the water broke apart in spring, she felt how precarious this place had just become: a risk to move, a risk to stay.

This ledge led to left and right. Instinct took her loping to the right and upward. When the hillside began to quake, she scrambled away from the vibration, moving toward quieter ground — until the new ground quaked and she had to change direction and move faster to new ground again.

She felt it: now Perrin ran and climbed beside her, crying out in terror as they went.

Nu ran as fast as her clumsy boots would permit, laterally, and climbed whenever she saw an opening vertically.

Perrin climbed nimbly too, crying out her grief.

Nu didn’t look below. But she heard the thick Artic ice crumbling away beneath her, melted by the warmth of spring…

She scrambled forward, then tripped and fell face-down on a flat place.

Hugging the ice as it rocked, she felt the quaking slow abruptly and cease.

The ice had become ruddy Martian ground again. Up she jumped, though, ready for the next quake. Perrin leaped up too, crying loudly but with less fright.

Now there was no more quaking or rumbling. They waited together a long time, prepared to run.

What do you feel?

Perrin here beside me. Her terror is leaving her.

When at last Nu turned her eyes downward, the landscape below had changed. The ravine was shaped differently now.

After a long quiet, she and Perrin climbed down together, patiently and carefully.

At the bottom of the ravine there were piles of jumbled rock turned at all angles, many of the broken pieces huge. All of them were sharp; Nu and Perrin found them difficult to climb over.

The two traversed the ravine floor, climbing up and down the shattered skin and broken bones of the Martian rock with respect. But something was different about the rock surfaces over by the narrow end of the ravine, where Nu had been yesterday. She and Perrin stopped climbing over them to stand and look.

Over there, many of the fallen rocks seemed to have patterns. As they came closer it was clear that the patterns were organic shapes, the unmistakable prints of ancient life. Still closer, the shapes resolved into ferns in one spot, bunches of grasslike reeds in another, and oddly shaped spike-edged leaves.

Nu forgot Perrin in her excitement. She took photos with her wrist camera. What a rich find for a paleontologist, she thought. Then she reached outward with her feeling and found Perrin again, wandering nearby.

What do you feel?

Her joy. She is in love with these prints of life.

Perrin drifted in and out of them, happy.

Nu sent images of a few of the best, attached to a message she sent to Brand: “Perrin’s legacy. She was right, many fossil prints here.” Knowing that Brand, the goodhearted dispatcher, would broadcast the news to the entire colony.

Let the Corporation ship her home now. At least Perrin’s spirit could be happy and not wander in the dark anymore. Nu would not be weighted by a failure of responsibility for her.

Hunger had caught up to her, but she wasn’t even going to think about what must have happened to her kite in this slide. Supper might be buried under a thousand kilotons of rock. She would have to request help and a rescue, neither of which would add to her professional reputation right now.

Instead, she leaned on one huge slab, a freshly broken piece of the outer skin of Mars, gazing at the cliffside.

The ritual began automatically. What do you see?

A fish. She spied her find from yesterday, the big almost-fish fossil print over there near the bottom of the cliff. Nu climbed and scrambled patiently forward over human-sized chunks of fallen debris, wanting to look closely at it again.

Today it appeared more like a fish than it had yesterday. Maybe because today its ancient scales looked shiny.

What do you see?

Abruptly she saw what was before her: the rock around the fish was stained with seeping liquid, and the ground below it too was turning from desperately dry dust to wet stuff. Martian mud? The liquid trickled past her downhill in a long stylus-thin stream that lost itself in the rockpile of the ravine.

Impossible. Not frozen, steaming a little in the frigid air: it must be thermal. She sank to her knees, awed, watching the tiny streamlet closely. Seeing it clear gradually and widen.

Seeing in it future fish swimming, future plants growing, riches that would not be carried off, but stay here and bring life back to this place. Impossible and possible had just met.

After a while she thought to thank Perrin and the gods of her childhood.

Finally, she sent a new message to Brand:

“Inform British Science Three and Corporation that Perrin and I have discovered an underground source of water, now visible as a spring at this location and timestamp, images attached.”