“Damnit! The exit’s closed!” Ben snarled, looking ahead to where flashing blue and red lights proclaimed a recent accident.

Sylvia thought that she knew why her not-quite-fiancé was so upset. They had an appointment to look at a house that Ben assured her was a great buy. Sylvia thought that his asking her to come with him marked a time when that “not-quite” would become “fiancé.”

“I’ll take the next exit,” Ben thought aloud, “and call to reschedule our appointment.”

Sylvia’s heart warmed at that “our,” but she didn’t offer to make the call for Ben. That would be presuming, and she’d learned so long ago that she’d forgotten the original lesson that she should never presume. Bad things happened when you did.

Grumbling about “hot prospects” and lost opportunities, Ben joined the file of those taking the impromptu detour. To avoid the crush created by those trying to get back on the freeway, he turned down a shady residential side street. He pulled his sport sedan up to the curb in front of a lovely older home whose neatly manicured lawn and well-tended mature shrubbery spoke both of money and of love.

Without speaking to Sylvia, Ben took out his phone and hit an icon. Fingers drumming on the steering wheel, he waited impatiently for his call to be answered. Not wanting him to see her worry, Sylvia looked away, toward a flash of motion. A dog had come around the side of the house and was galloping across the sloping lawn toward the car. It was a big dog, stocky and a touch overweight, mostly golden retriever, Sylvia thought. He moved with such energy that it wasn’t until he arrived at the side of Ben’s car that Sylvia glimpsed the grey on his muzzle and realized that the dog was quite elderly.

Ben left a message, and punched another number. Listening, he glowered absently at the dog. When the dog made as if to rear up and put his paws on the car’s newly washed and polished side, Sylvia reached to open her door.

“I think Fido there thinks we’re visitors,” she said to Ben. “How about I take him up to the house?”

Ben nodded absently. “Don’t take long. I might need to leave right away.”

“I won’t, but I’d hate for this old sweetie to get hit. I have my phone. Call me when you get through and I’ll hurry down.”

Ben gave a distracted wave. Taking this for permission, Sylvia got out. The dog was absolutely delighted. After licking her hand, he pranced ahead, leading her up the artistically curving flagstone path that led through the shrubbery, toward the front door.

As she followed, Sylvia was overcome by a strange sense of familiarity, something like homecoming. It was ridiculous, of course. She’d spent her life in a series of more or less decent apartments, first with her mother, later on her own. The house Ben was shopping for would be her first time living in a house. But she kept seeing things she knew: the flagstone with the crack shaped like a lightning bolt, the moss-covered urn that ornamented a turn in the path, the angle of an oak’s limb. All these seemed friendly and familiar.

I probably saw a painting or photo of this place. Maybe it’s a historical landmark. George Washington slept here or something. Maybe I came on a school trip.

The dog pranced up to the front door and was bouncing as old dogs do when they can’t get up on their hind legs.

“Want me to ring the doorbell?” Sylvia bent to ruffle the dog’s ears, remembering too late that she’d get golden-brown dog hair on her neat outfit. Guiltily, she looked down at the car to where Ben remained intent on his phone. Hurriedly, she pressed the shiny brass doorbell, a custom model shaped like a four-leafed clover. As if responding to the melodic chime, the dog gave a happy woof deep in his throat, then darted around her to the left. When Sylvia swung around, she saw that a man —silver-haired, clearly elderly, although not in the least frail— had rounded the corner of the house.

The man held a dog harness in one hand, at the sight of which her canine friend’s ears and tail drooped, although his plumed tail didn’t stop wagging. The old man’s eyes widened slightly when he saw Sylvia. For an odd moment, she thought that he had recognized her in the same way she had recognized the house. Certainly, when he spoke it was as if to a long-time friend, rather than to a stranger on his doorstep.

“So, it was you Caun heard. I was putting him in his run when he bolted off. I always worry he’ll go out in the road. He’s not as fast on his feet as he thinks he is.” The old man gave a rueful smile. “Neither of us is these days. Thanks for bringing him back.”

Sylvia was normally shy, but she found herself responding easily. “More like Caun brought me. He came leaping up to the car” —she gestured with her head— “as if we were expected guests. My boyfriend’s trying to reschedule an appointment, so I followed the dog up here.”

Impulsively, she continued, “You have a lovely house. I feel as if I’ve seen it before. Is it maybe famous or historical?”

For a flicker of a moment, Caun’s human’s expression was hard to read, then he smiled. “Not that I know, but it’s been in my family for generations. I’d be happy to show you around, but you said you have an appointment?”

“Let me check with Ben,” Sylvia said, pulling out her phone. Then, after a brief exchange, “I have time. He’s still trying to get us rescheduled. By the way, I’m Sylvia.”

The old man offered her a short bow. “I’m Graham. Why don’t we walk around the side and look at the gardens. I think you’ll like them.

Compared to the formal study in cool green and shadow that was the front yard, the softly rolling back garden was almost shocking. Mature rosebushes and an intricate perennial herb garden testified to the age of the landscaping, but these were almost overwhelmed by garden sheds disguised as a playhouse-sized turreted castle, a “thatched” English cottage, and even a two-masted sailing ship. The generous run surrounding Caun’s doghouse was concealed by a “log” palisade. The doghouse itself looked like the popular conception of a Western fort.

“Oh! Wonderful!”

“My late wife’s idea,” Graham explained, “but I’ll admit, I rather like the view. The back patio is my favorite place to sit and read.”

Sylvia started to say something about how the grandchildren must love playing here, but caught herself in time. Despite the fanciful landscaping, there was no evidence of children: no scattered toys on the lawn or balls rolled under the hedge. A lawn tractor resided in solitary splendor within the castle, even though there was ample room for bicycles or other kid-type vehicles.

“Shall we go inside?” Graham asked after they had finished walking around. He opened a door into a hallway, then politely held it for her while Caun led the way.

To one side, Sylvia glimpsed a nicely appointed kitchen, neat and clean in a way that suggested it wasn’t much used. Graham skipped this and headed toward the front of the house.

“My home office is in what used to be a parlor, but an office is much more useful. My assistant, Pamela, is working in there.” He indicated a closed door. “We won’t bother her. This time of day, she’s always in a hustle to get things ready for the mail.”

Sylvia admired the comfortable workspace, thinking how different it was from the crowded windowless cubicle she called her own at the state university, where she did clerical work. There was plenty of room for books. A large basket that Caun showed her was his by getting into it then out again, rested in front of a now dormant fireplace.

“This door opens into the entry foyer,” Graham explained, continuing the tour. “The formal living room and dining room look out onto the back garden. I think it says something about my ancestors that they put a library at the front of the house, across from the parlor.”

“I’m with your ancestors,” Sylvia said, noticing that showpiece that it was, this was definitely a working library. Bright contemporary novels shared the shelves with leather-bound classics. “I’d love to sit and read in that bow window.”

“That’s my favorite place, too,” Graham said. “Have you read the new edition of Blake, the one with the reproductions of his art?”

“No, that sounds fascinating.”

As they talked books, Sylvia looked out the front window. Strangely, the yard didn’t look at all familiar from this angle, nor had the interior of the house.

I must have seen it in a painting or photo at the university, she decided.

When they finished their tour, Sylvia excused herself. Ben hadn’t called, but it would be better if he didn’t need to. Poor guy was probably frantic and could use some moral support. Even so, she felt reluctant to leave. The interior of the house may not have seemed familiar, but she’d felt an instant rapport with Graham. They’d liked the same books, and laughed at the same things, causing Caun to wag his tail, as if Sylvia was a pair of slippers or a newspaper he’d fetched without being asked.

“I’ll show you out by the front door,” Graham said, “but at least let me give you my card. Perhaps you’d like to visit again, maybe browse some of the older volumes in the library. I’ll make sure Pamela knows you have my permission.”

He hurried into his office and, when he came out, he had not only the promised card, but a pair of pendants shaped like golden retriever heads in profile.

“For rescuing Caun,” Graham said, “and, if you can wait one more moment, I have two copies of that Blake omnibus I mentioned.”

When he went into the library, Sylvia held the pendants up to the light, wondering if Caun had been the model for them. Something about how the ears perked and that the dog was smiling, rather than looking aloof and noble as was more typical, made her think he had been.

The sharp click of heels on the tile floor announced someone other than Graham. A woman in her forties or fifties with “executive assistant” in every line of her trim body and understated turnout came around the corner from the direction of the office. She looked at the pendants and said dryly, “Don’t just toss those in your jewelry box. They’re valuable.”

Without another word, she placed a thick stack of envelopes in the mailbox and departed.

Sylvia stared at the pendants, about the size of a nickel, they were gold-colored, but surely not gold. The dog’s collar was set with green stones.

Surely these are cast resin and crystals, not real gold and gems.

Graham appeared at that moment with the promised book, a nice trade paperback, not in the least costly. The modest nature of the gift reassured Sylvia that the woman —certainly the Pamela who Graham had mentioned was his assistant— had been teasing her for some reason. Still, Sylvia might have given the trinkets back if, at that moment, her phone hadn’t signaled a text from Ben. There was no message, only a thumbs up icon.

“Got to go!” she said, bending to give Caun a pat, and narrowly resisting the urge to give Graham a hug. Graham opened the door for her, and she all but ran down the curving path. “Thank you! I had a wonderful time.”

She didn’t look back until she was in Ben’s car and he was pulling away from the curb. Graham stood in the doorway, Caun all but sitting on his feet, the pair framed by a house and landscaping that Sylvia felt certain she had seen before.

A week went by before Sylvia gave in to the impulse to return to Graham’s house. Her excuse to herself was that she owed Graham a return gift. She knew perfectly well she could mail something but, in the end, she baked a batch of cookies and put them in a tin ornamented with a silhouette of a dog who reminded her of Caun. Her plan was to place the cookies on the doorstep along with her thank you note, then leave.

However, when she pulled her third-hand car up to the curb, there was Caun, tail wagging in greeting. Remembering how Graham had worried about the old dog getting hit, Sylvia grabbed the gift bag and let Caun “fetch” her up the walk and around the house to where Graham was clipping the roses.

“I didn’t mean to bother you,” Sylvia began, but Graham waved her attempted apologies aside.

“I’m just about fed up with thorns. Would you put Caun in his run? Can’t reward him for running off, even if I am pleased with what he found. Tell me, what did you think of that Blake?”

With that, nothing seemed more natural than that they settle on the patio. Graham brought out coffee, opened the cookie tin, and they discussed Blake. Sylvia kept meaning to bring up the pendants, which she was wearing under her top for luck, but somehow she never found an opening.

At the end of her visit, Graham loaned her an annotated collection of Yeats’ plays. Of course, that meant that Sylvia had to return it. This time she called in advance and made an appointment with Pamela, so Graham could avoid her if he wished, but Graham and Caun were there to greet her. Somehow their meetings became a regular thing, once or twice a week. Sometimes over lunch or dinner, always very proper. Sylvia often brought something she’d made, and after a while Graham encouraged her to use the kitchen.

Ben wasn’t thrilled, saying that hanging out with rich people would make Sylvia discontented. She didn’t try to explain that she didn’t feel that way at all, since Ben wouldn’t believe her. Ever since her mother’s death, Sylvia had been without family. These days Graham, even more than Ben, felt like family. In her thoughts, although never aloud, she called him “Grandpa.” He, in turn, treated her rather like she imagined a grandfather would, although she’d never known any of her grandparents— or her father, for that matter.

Pamela lost her frosty air toward Sylvia, often joining them for lunch and adding formal and thoughtful comments about whatever book or movie they were discussing. Pamela didn’t exactly unbend, but as she never unbent, even for Caun, Sylvia wasn’t offended.

There was one person who made clear that not only did he have no time for Sylvia, he actively disliked her. This was Randall, Graham’s only child, a man in his forties. Superficially, Randall resembled Graham but, as he was as sullen as Graham was warm, they didn’t seem much alike. Randall didn’t live with his father. However, as he was involved in the business in some way —Graham never mentioned what, and Sylvia didn’t ask— he was often by the house.

Randall was the only person Caun ever growled at. With more courage than sense, the old dog would often place himself between Graham and Randall. When Randall’s dislike of Sylvia became more obvious, Caun set out to protect her as well.

As summer flowed into autumn, it seemed as if the situation might go on unchanged indefinitely. Ben had not proposed, not even after buying a neat little house. Sylvia had tried to get him to come with her to Graham’s, but either his job or the new house kept Ben constantly busy. Sylvia didn’t push him, and hoped he’d change his mind. Then, one afternoon in late September, everything was altered by a few chance words.

Sylvia had been invited for lunch and, as had become the custom, she was going around to the back door. As she did so, she heard Randall’s voice coming out through the partially open window of his father’s office.

“I’ll be going. I saw on your calendar that the little gold digger is due. I have no desire to see her. I don’t know who disgusts me more: her— or you!”

“Sylvia is not a gold digger!” A weary note in Graham’s voice told Sylvia that they’d had this argument before. “As for the sight of her making you sick— you only have yourself to blame.”

Randall retorted, but Sylvia pressed her hands to her ears to block the words. She wanted to run, but fear that she’d encounter Randall kept her frozen in place until she heard the front door slam and the purr of Randall’s expensive sports car starting up. She would have run then, but Caun was there, pressing his nose against her leg and whimpering. Then there was Graham, his expression worried, shoulders slumped, looking old and tired.

“Please,” he said, holding out his hand. “We must talk.”

Sylvia followed him into his office. Graham closed the window and used the intercom to contact Pamela. “No interruptions. Not for anything at all.” The meekness of Pamela’s reply made Sylvia wonder how much she’d overheard. Graham motioned Sylvia to a chair, then sat behind his desk. Caun moved restlessly between them, then sighed and collapsed in a fluffy heap where he could watch them both.

“Sylvia, I have a great deal to tell you— all of which you’re likely to find hard to believe, so I won’t ask you to do so. All I ask is that, because we’ve been friends, I hope you will listen.”

Sylvia nodded stiffly. Graham steepled his fingers and began. “I have good reason to believe that you are my granddaughter, Randall’s daughter. Since this will be easy enough to confirm, I want to move to the impossible part of my tale.”

With a heroic effort, Sylvia managed to nod again.

“Back in the early 1800’s, one of my ancestors saved the life of a rabbit who was being pursued by something that looked like a fox, but was not, any more than the rabbit was actually a rabbit. In return, the rabbit reached up and pulled off one of her front paws and said to him, ‘I give you this lucky rabbit’s foot, but I must warn you, good luck is never granted without a cost. In rare cases, good luck is without consequences, but more often than not good luck for one person means that someone else suffers, not necessarily bad luck, but lesser luck.’”

Graham paused for breath. Although Sylvia had meant to stay quiet, she heard herself speaking, as if this was one of their usual chats about a poem or a song.

“Like when you’re playing a game and one person always gets the good rolls of the dice. He isn’t doing harm, but his good luck means that everyone else has to settle for second place or worse.”

Graham visibly relaxed. “Like that and more. The rabbit’s gift was given on the terms that the ability to invoke good luck —and in turn to cause bad luck or lesser luck— would last until the family line ended. I won’t claim that all of my ancestors were ethical, but early on the lesson of what happens when good fortune is gained at the expense of others was learned. We also learned that great good luck needed to be balanced, often by no luck at all. As for luck that caused bad luck for others, well, someday I’ll tell you the tales, even as I told them to Randall, for all the good it did me.

Sylvia made a little “go on” gesture.

“Although we would have loved to have more, my wife, Lily, and I had only one child— Randall. When he was born, we decided that if we were to invoke the rabbit’s gift, we would be inviting very bad luck indeed. Then, when he was five, Randall became very ill and we were told to resign ourselves to losing him. You can guess what I did.”

“Used the rabbit’s luck,” Sylvia said, never doubting she was right.

“And Randall lived and grew up. When he was in his late teens, he realized that my stories were history. He was furious when I told him that we had already used our allotment of good luck when we saved his life. He raged as only an indulged —yes, I’ll go as far as saying spoiled, literally rotten— child can. He said that it was unfair that he had to make his own way when I’d always had the rabbit’s luck to make my life easy. Nothing I could say would make him believe this wasn’t true. He was certain that my mother had ‘cheated’ for me, and I had never known. I will spare you the details but, in the end, he told me that if the family heritage meant more than his son’s happiness, then he would get even by making certain that the family would end with him.

“Then, one day as I was reading in the library, I witnessed a confrontation between Randall and a young woman. The woman had a little girl of about five with her— a little girl I feel certain was you. Despite the woman’s pleas that he acknowledge his daughter, Randall sent the woman away with such vicious threats that I feared even to look for her. All I could do was hope that luck would someday bring her back to me.”

He smiled sadly. “And, no, I didn’t do anything to help that luck along. I just had to hope. When Caun brought you up to the house, I recognized you as soon as I saw you. You look so much like your grandmother, my Lily, did at your age— you sound like her, too.”

Sylvia’s heart beat so hard that it drowned out Graham’s next few words. Caun came over and placed his head in her lap, and gradually she calmed enough to hear what Graham was saying.

“…my will to include you. It should be done before Christmas, although there’s always a slowdown in getting anything done between Thanksgiving and the end of the year.”

Sylvia jerked her head up. “Oh, no! I couldn’t let you do that. Then I really would be a gold digger like Randall called me.”

“Randall has no say in this,” Graham said sternly. I won’t disinherit him or do anything petty, but you are my granddaughter— and my friend. We are friends, aren’t we?”

Sylvia didn’t know what to say. If Graham had recognized her from the start, were they really friends or was she just a pawn in Graham and Randall’s power games? Then Caun looked up at her with pleading brown eyes and Sylvia realized she didn’t want to let her apprehension transform the wonderful events of the last several months into a lie.

“We’re friends, Graham. I’d be happy to accept the sort of gifts friends give friends, but I insist on doing a DNA test so you don’t let a chance resemblance lead you to something you might regret.”

“More than fair,” Graham said. “I should do one, too, so there’s something to compare your results to.”

“You never did one,” Sylvia asked shyly, “looking for that little girl or some other relation?”

Graham’s smile was bittersweet. “Ah, my dear, now you can see how easy it is to trust to luck and forget that there are other ways to deal with one’s problems.”

On the day that she learned that she and Graham were definitely related, Sylvia didn’t call ahead. Instead, immediately after work, she drove over to Graham’s house. As she got out of her car, she heard Caun howling— a sound very unlike his usual exuberant barking. Panicked, Sylvia ran up the flagstone path and around the side of the house. Graham lay sprawled on the patio, unconscious, his head bloody, his breathing shallow and erratic. Caun’s kibble spilled around him in a parody of a halo.

Pamela was kneeling next to Graham, talking into her phone in a calm, efficient manner that was quite at odds with her terrified expression as she attempted to staunch the blood welling from Graham’s head with her sweater.

“Please hurry. He looks very bad. Yes. His granddaughter has just arrived. She’ll help.”

Disconnecting, Pamela said, “Five to ten minutes at least. They said given the cold weather and the ice on the patio, we’d best move him inside, even at risk of back injury.”

Sylvia darted into the kitchen. She pulled the oilcloth cover from the small table where they often had lunch in preference to the grand dining room, then ran back outside.

“We can try to slide him,” she said, and Pamela nodded.

The next few minutes were a blur. The EMTs didn’t say much, but it was clear that the situation was bad. Graham had apparently slipped on an icy patch on the patio. When he’d felt himself falling, he’d dropped the bowl of dog kibble and tried to catch himself, with the result that he had likely broken bones in his arm or hand. Despite this, his head had hit hard, possibly fracturing his skull. Prioritizing speed, they’d strapped him to a stretcher and taken him away.

Before the EMTs had arrived, Pamela had given Sylvia a quick briefing.

“Randall is next of kin. Given how he feels about you, I don’t think you’d better go to the hospital just yet. Luckily you’re here and Caun likes you. Can you stay and do what you can? I’ll go to the hospital, since I doubt Randall knows anything about his father’s medical history or insurance.”

Only after she was alone with Caun did Sylvia’s panic ebb enough for her to think about what Pamela had said. Had there been a stress on that “luck-ily”? How much had Graham confided in that competent woman? Or maybe she’d simply overheard enough of Graham and Randall’s epic arguments to arrive at her own conclusions?

Sylvia went out. Caun had stopped howling, and now he paced restlessly inside of his run. She looked at the blood on the patio. Should she try to clean up? Feed Caun? Call Ben? As she stood there, Caun barked, the sound sharp and imperative, very different from his frantic howls earlier or his usual greetings.

Almost in a dream —which was probably shock— Sylvia walked over to Caun’s run and undid the latch to open the gate of the palisade-style fence. Caun didn’t come galumphing out as she expected, especially given that he’d never been known to overlook a dropped morsel and his dinner was scattered on the patio. Instead, he stood, gaze fixed on her. She walked into the run and ruffled his ears.

“Dreamlike” is often used to mean an ethereal state, vague and floaty, but in truth dreams can be more intense than waking. That is why people wake up screaming from a nightmare. Sylvia felt that intensity now. Luck. Graham’s family had luck. She was Graham’s family, not only by the dubious ties of genetics, but by their mutual desire. Could she? Should she? Graham had made it clear that using luck was problematic. Would he even want her to try? And how was it done? Hadn’t he said something about a lucky rabbit’s foot? Where was it? Hidden, obviously, or surely Randall would have used it.

An invisible clock started ticking inside her head. Was that the sound of Graham’s life running out? She’d never been very decisive. Could she decide this on her own? She could call Pamela. Maybe she’d have ideas.

Sylvia dropped to her knees and wrapped her arms around Caun’s neck.

Tick.

Hidden somewhere Randall wouldn’t go. Caun didn’t like Randall. His doghouse. A fortress that never seemed to keep Caun in. Was it meant to keep someone out?

Tick.

A pair of golden pendants, modelled after Caun.

Tick.

On hands and knees, Sylvia crept into the roomy kennel. It smelled so strongly of old dog that she had to fight an urge to back out.

Tick.

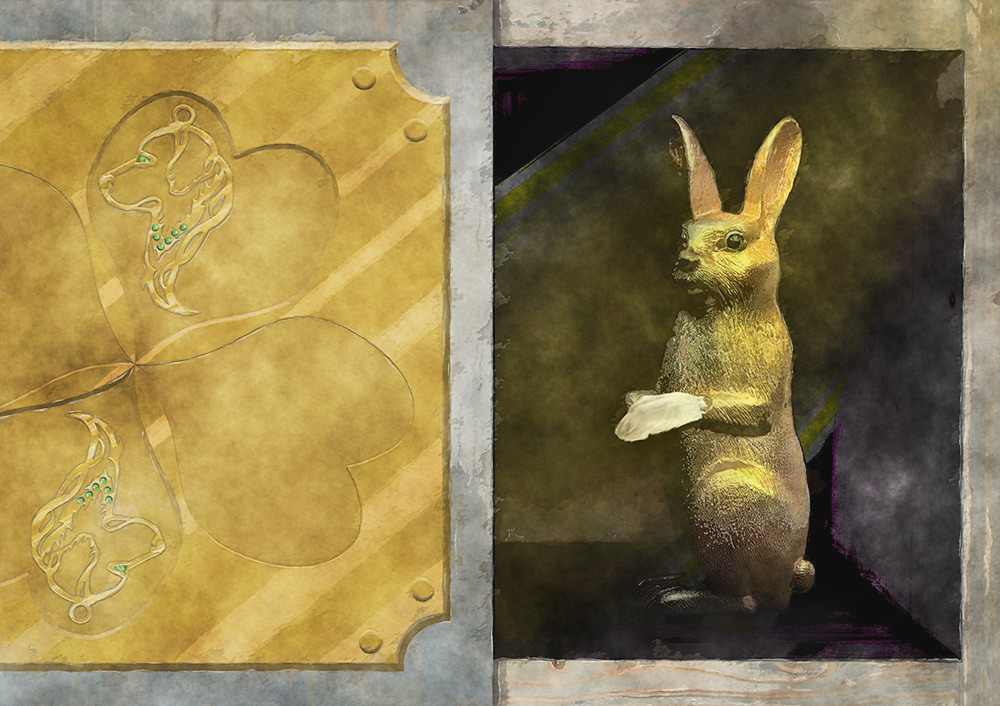

At the back of the kennel, hidden by the dog bed, Sylvia found a brass plate embossed with a four-leaf clover. It instantly reminded her of the button for the front doorbell, but this wasn’t a button. Instead, two of the clover leaves set diagonally to each other were depressions. She probed and pressed into them with her fingertips, but nothing happened.

Tick.

Caun paced restlessly behind her, his body temporarily blocking the sunlight. When light returned, it brought insight as well as illumination. She grabbed the chain around her neck, pulling out the two golden pendants. After a little trial and error, she found how to fit them, one each into a lobe of the four-leafed clover.

Click.

Tick.

A panel slid aside, revealing a sculpture of a rabbit sitting up on her haunches, one paw extended. Most of the sculpture was golden, but the extended paw was furred, as fresh as if the rabbit was alive.

Tick.

As Sylvia reached to touch it, a storm of faces, a thunder of voices interposed themselves making it impossible for her to move.

Randall: “…little gold digger. She just wants to make sure he lives to put her in his will.”

Ben: “…getting so above yourself I hardly know you. Aren’t I good enough for you anymore? Where will I fit in your posh new life?”

Mama’s voice: “Nothing good comes from mixing with these people. Stay away.”

Graham’s voice: “I spent my luck to save my son. All I got was ingratitude and hatred. Do you think I want to live with the guilt of you wasting your future luck so an old man can have a few more years— crippled up, too, no doubt?”

Pamela, as if overheard: “Signed and witnessed. You’ve done well by her: the dog, the house, and a few millions to maintain both and with plenty to spare.” Dropping to a whisper, “So you can die in peace.”

Tick.

Tears blurred Sylvia’s eyes. She pressed her hands over her ears. How could she decide for Graham? No matter what she did, someone would be angry with her. If Graham died, Randall would fight any new will— if there even was one. She knew she’d never be able to fight back, so Graham would be angry, too. What would Ben think? That she should go for the chance of money or relinquish it for love of him?

Tick.

A voice that was almost her own added itself to the storm, so soft that Sylvia had to strain to hear it.

“Luck is not a wish. Good luck can be someone’s bad luck. Bad luck may be someone’s good luck. What do you want your luck to be?”

Tick. Fainter.

Sylvia thought. If Graham died, she could escape all the anger, go back to her peaceful life, but…

What would happen to Caun? Randall wouldn’t care for the old dog, and she wasn’t allowed pets in her apartment. Ben would never ask her to move in if she had a dog.

Decision made, Sylvia reached for the rabbit’s paw. “Luck for those without voices, and so I can learn to raise my voice. Good or bad, I’ll take it. If it matters at all, I’ll give Caun a home.”

Tick. Then quiet. Then the ticking resumed, faster and stronger. Tick, tick, tick.

When Pamela called, Sylvia was sitting in the kitchen with Caun. She’d made them both dinner and done her best to get the worst of the blood off the flagstones.

“Graham’s not out of danger, but he’s stabilized,” Pamela reported, her voice warmer than Sylvia had ever heard it. “A broken forearm, but his skull wasn’t cracked and we didn’t hurt his back moving him. They’re monitoring for all sorts of things, so he’s likely to be in the hospital for several days.”

She paused to let Sylvia ask questions, and when she’d answered them, Pamela went on.

“Graham keeps asking for you. He gets so agitated that the medical staff have overruled Randall’s protest. Can you come? I should warn you. Randall’s here, and he is not feeling friendly.”

“Luckily,” Sylvia said, “I’m not going to let what Randall thinks get in my way.”